State of Confusion

featured in the Oxford American

I wasn't there at the time, so I have no way of knowing for certain, but I believe the trouble all started with the name. Naming a baby is damn-near impossible. But naming a state? Who does such a thing? They don't even have those handy books you can flip through for inspiration. It really is uncharted territory.

But still, they got some good ideas down. A handful of decent options, including Columbia, Allegheny, Monongahela, Potomac, and the one that was actually on the charter at one point—Kanawha. Then they got the yips. Forging a new state was a pretty bold maneuver—especially since they were carving it out of a rather popular and populous state already in existence. Was it necessary to come up with an entirely new name as well? Couldn't there just be some type of happy medium that didn't confound everyone? And there it is. The problem. In the spirit of making things less confusing for themselves at the time, they forced countless generations to have endless exchanges that go something like this:

"I'm from West Virginia."

"Oh really? I have a cousin in Roanoke."

"That's in Virginia."

"What do you mean?"

"I'm from West Virginia. It's a different state."

"Really?"

"Yes."

It's frustrating to come from a state that most people don't even know exists. The only thing worse is when they do. They get that mischievous twinkle in the eye and then, out pour the jokes. The barnyard jokes, the banjo jokes, and everyone's favorite, the incest jokes. I'm not sure what response people are hoping for when they accuse me of screwing my sister, but I can assure you it never endears me toward them. And I don't even have a sister. But these sad stabs at humor can't be unique to West Virginia. I'm sure it happens to people from all sorts of Southern states: Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Kentucky. Hell, to be perfectly honest, I've made those sorts of jokes about people from Kentucky. But it all leads up to a bigger question. These are attitudes about the South. So, is West Virginia a part of the South?

The geography would seem to say, yes. There's the Mason-Dixon line, forming the better part of the northern boundary of West Virginia. It's common knowledge that everything below the Mason-Dixon is the South. But then there's Maryland. Every square inch of that state lies below the line, and there isn't a soul on earth who would claim to be in the South while traipsing through Baltimore. So, the Mason-Dixon isn't exactly fool-proof as a Southern indicator.

You could argue that West Virginia belongs to the South through a simple process of elimination. It's not the Northeast. We're not high-falutin' enough to hang with that crowd. And it's not the Midwest. We're a tad too... colorful for their tastes. So we're below the Mason-Dixon. We're not the Northeast. And we're not the Midwest. Riddle cracked, the scores have been tallied. West Virginia, welcome to the South!

Except. Well, there is that one other thing.

The Civil War was serious business. War always is. People on one side didn't generally care for people on the other. The only thing worse than being the enemy was switching sides in the middle of the fight to become the enemy. Which is exactly how West Virginia was born.

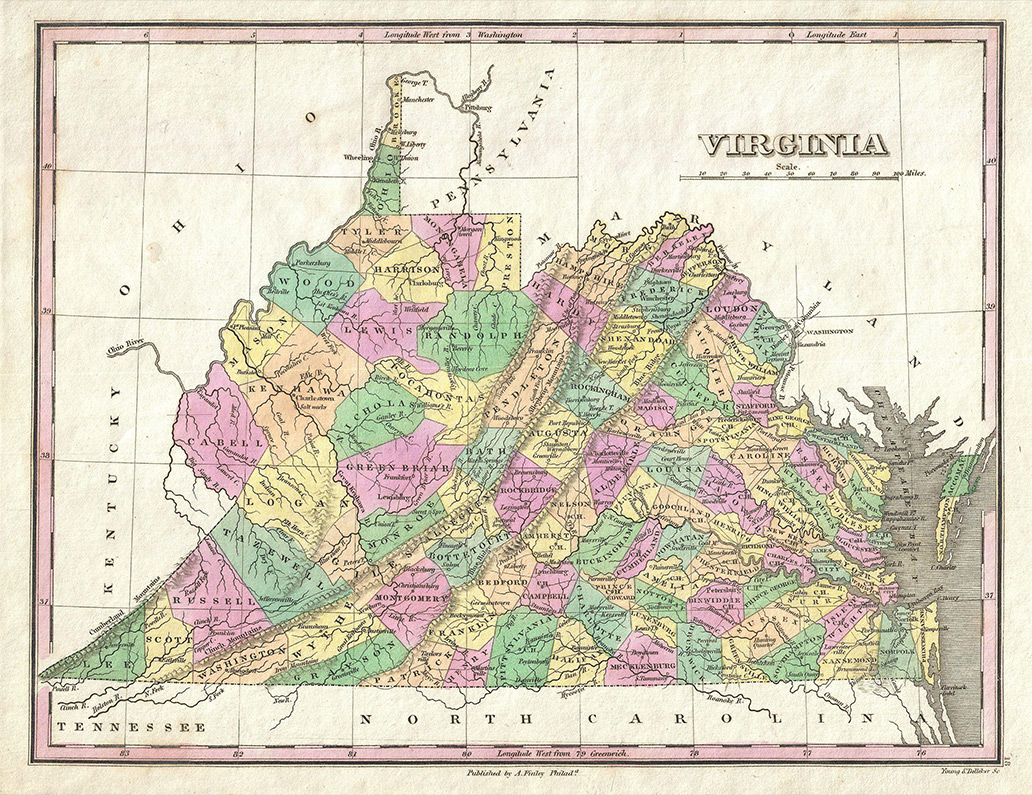

Virginia was a big state. The biggest state in the Union for a long while. In fact, it held that status until just twenty-five years before the Civil War erupted—before they started doling out boxy parcels of land out west and calling them states. But, from the very beginning, there were two different cultures emerging in Virginia. In the southeastern part of the state were the blue bloods. It was mostly fields and farms and coastal lands. In the northwest were the mountains. An entirely different place, populated by an entirely different people.

You can't talk about West Virginia without talking about the mountains. The science books say the land was once flat. But if you've ever stood on a high peak and watched the hills rolling out—piled atop one another, mellowed with age, and quiet—you'd be hard-pressed to drum up the necessary mixture of imagination and trust to ever believe that. The mountains are there and, as far as any human history is concerned, always have been. They were certainly there in the early days of America when people were deciding where to live. One surveyor, in examining parts of what would later become West Virginia wrote, "It seems very strange that any person should have settled there at that time when the whole country was almost vacant."

But that's the point, really. People had their choice of the entire country, and some of them chose to live there. In the mountains. It may have been one state, Virginia, but it was clearly occupied by two very different sorts of people.

This leads some to say that the separation between Virginia and West Virginia was preordained to some degree. There was different land, different societies. Even the rivers flowed in opposite directions. But I'm not sure I buy it. Conflicts have always existed between different regions in the same state. I live in Northern California now, and it's rare that anyone here can drum up a kind thing to say about the sort of folks who live too far south of the thirty-eighth parallel. But even so, we manage to continue on as one state. It took guns, bloodshed, and a country ripped apart to provide catalyst enough to make Virginia finally come apart. The only time in all of U.S. history that a state has split in two.

So the Civil War starts up. The bumpy part of Virginia raises its hand and asks to be excused from secession. In doing so, it actually secedes from one of the original thirteen colonies. And the mad-dash land grab begins to form the newest member of the Union. It starts with the obvious counties, the northern ones that have more in common with Pittsburgh than Richmond. Then it spreads. A few counties here. A couple more there. Until West Virginia is formed, looking more like an ink blot than a state. But in the end, everyone—save Virginia—seems relatively happy. Lincoln gets a fresh batch of allies for the fight. The mountain people get their own state, with their own government, and their very own name.

But dammit! I know there was a lot going on. A war being fought. Some pretty shady circumstances under which to form a new state. But, if they were dead-set on calling the place "West Virginia," they honestly should have thought it through a bit more. See, the name implies it sits to the west of Virginia. A little north, maybe, sure. But entirely to the west. Unfortunately, that isn't the case. The current state of Virginia actually extends ninety-five miles further west than the westernmost part of West Virginia. I don't care whose side you're on, this is an oversight. If, when they were grabbing land, they'd snagged just four extra counties in the bottom, left-hand corner, the name would have at least made a bit more sense.

But that's the way things seem to be in West Virginia. We're a bit of a black hole for all things conventional, tidy, and easily explained. Take, for example, the Presidency. Virginia proudly bills itself as the "Mother of Presidents." Eight U.S. Presidents were born there. Ohio forms our other largest border. They've managed to have seven Presidents born on their soil. To the north, Pennsylvania. They've had one. Southwest of us, that's Kentucky. They've had one, too. The only state that borders West Virginia that hasn't birthed a President is Maryland. And frankly, that's just a matter of poor timing. Spiro Agnew was from Maryland. If he could have held off just a bit longer on his resignation—outlasted Nixon by a few months—he could have been President. If only for an afternoon.

But, by the official count, that's seventeen Presidents born on the perimeter of West Virginia. Nearly forty percent of our Presidents to date. And not one born on our hallowed, hilly soil. I even checked to see if any of the Virginia Presidents had been born in a part of the state that later became West Virginia. Hoping for a de facto Presidency to which we could lay claim in some way. But alas, our mountainous terrain is—and apparently always has been—inhospitable to Presidential timber.

Which isn't to say we haven't had people born in the Mountain State who have gone on to do great things. Ask anyone from West Virginia to name the fame that's sprung forth from our land and you'll witness an eager litany that will both surprise and delight. Chuck Yeager (Take that, sound barrier!)—Jerry West (The NBA logo himself!)—Pearl S. Buck (Nobel Prize!)—Mary Lou Retton (Perfect 10!)—Bill Withers (That's right, we got soul!)—Don Knotts (!). Somehow it always ends up there. In our desperate hope to cram in one more name—to prove that folks go forth and make something of themselves from our fair state—we end our case with Barney Fife. Which, no offense intended toward the late Mr. Knotts, always seems to hurt the argument more than help it.

But that sort of "eager to please" attitude seems to come with the territory. We're a defensive people. Always have been. Coming from a state that was conceived in controversy doesn't make for a relaxed citizenry.

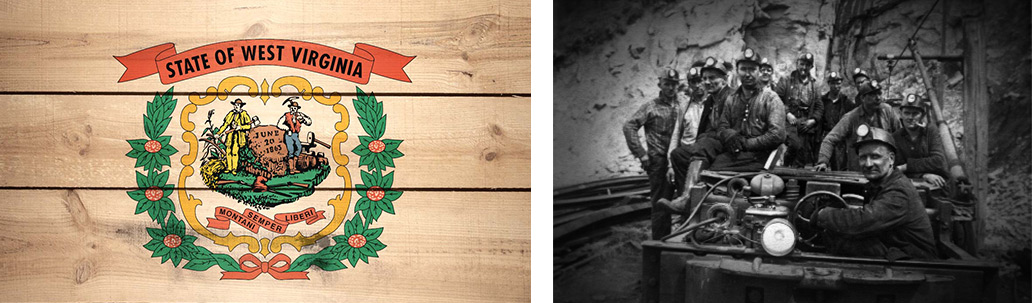

But there's more to it than that, of course. There are the jokes. The predilections. The seemingly unshakable poverty. Read any history of West Virginia and it plays like a Rodney Dangerfield act—without the laughs. People came in and took our coal, then went elsewhere to create true industry. They took our timber, then shipped it away to make furniture and floorboards and other goods to sell. They gutted our mountains for the minerals, then left us with industrial swimming pools filled with equal parts poison and regret.

You have to let these things happen to you, though. And, for the most part, West Virginia did. Partly out of trust. Partly out of hardship. Partly out of that timeless bringer of endless sorrow—greed. But greed exists on a smaller scale in a land like ours. The people who would sell the mineral rights to their land weren't hungry for a mansion or a yacht or anything as grandiose as that. They were hungry for some meat. Maybe a new stove. A little extra food to feed their families. They wanted to be able to stand upright for a while—let their backs straighten and rest—instead of hunkering over, or inside of, the land in an exhausting attempt to simply make ends meet.

I think this is part of the reason no President has been born in West Virginia. People are too busy working and loving and living in a forgotten land like ours. There just isn't enough time to picture yourself sitting in the White House. You'd honestly just as soon be sitting in your own house, enjoying what you've earned that day. Then, resting to earn up for the next. Older cultural, social, and economic conditions tend to survive—even thrive—in the mountains. They say if the world ever ends, you'll want to be in West Virginia. It'll take twenty years for it to catch on there. But that's the thing with deep roots. They tend to keep you off the cutting edge.

People have been taking their jabs at West Virginia since the day it was born. "To admit a state under such a government is entirely unauthorized, revolutionary, subversive of the Constitution and destructive of the Union of States." This from Jefferson Davis—a guy who tried to peel half the country away from itself, lined up armies, and started a war in order to do so. Even with that under his belt, he felt qualified to wave his hypocrisy in the face of a handful of mountain folk who didn't care to play along.

The South is probably the best place for West Virginia. The geography, the mentality, the accent, they're all a lot more Southern than not. But, due to the war between the states, we have an eternal asterisk next to our name. If we'd remained a part of Virginia, we would undoubtedly be considered a Southern state. But now, no one can be certain. West Virginia will likely always exist outside of geographic pigeonholing and regional arrangement. If history serves as any indicator, no one will be lining up to welcome us into their provincial fold any time soon. No one really wanted us back when we became a state. We were just warm bodies in a moment of national desperation. I know, when desperate, I've certainly been less-than-discerning about the company I've kept.

All I know is, if I'm less Southern than some of the people I meet, I'm a hell of a lot more Southern than others. Which leaves me in a unique spot. It's a small state, after all, so there aren't many who can proudly say, "I'm from West Virginia."

"Oh, yeah? I have a cousin in Roanoke."

"No, I'm from West Virginia. It's a different state."

"Really?"

"Yes."